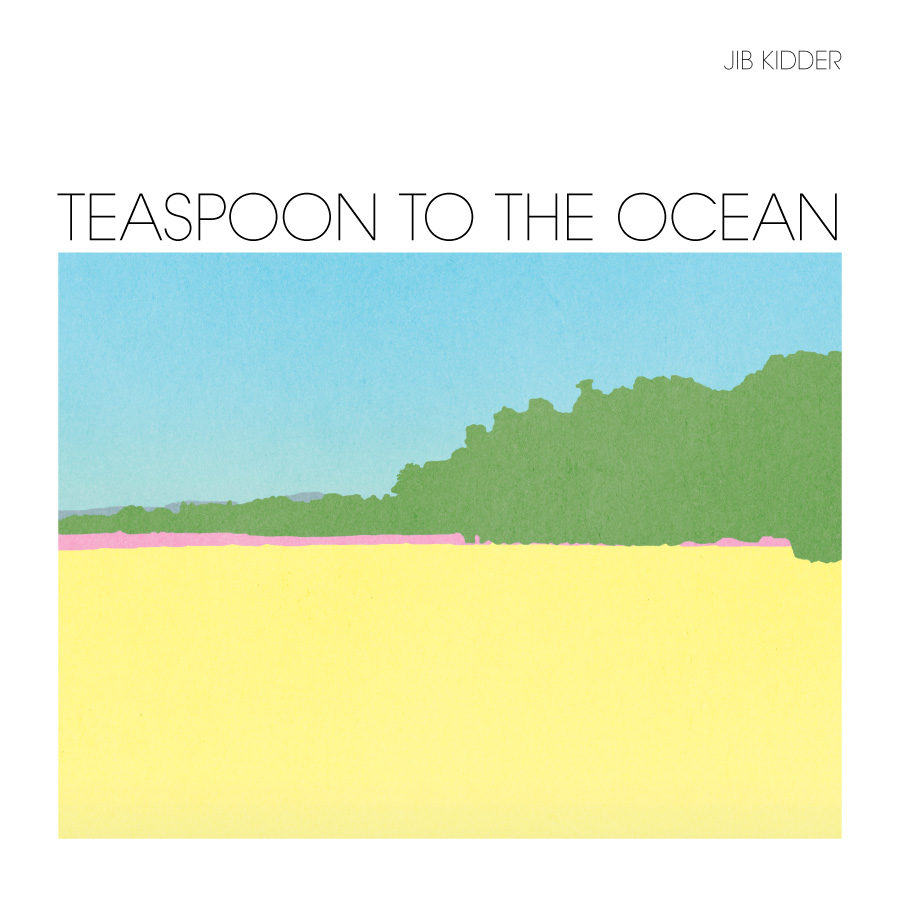

Teaspoon To The Ocean tracklisting:

- 1.Remove A Tooth

- 2. In Between

- 3. Appetites

- 4. The Waves

- 5. Situations In Love

- 6. World Of Machines

- 7. Dozens

- 8. The Many

- 9. Illustration

- 10. Melt Me

- 11. Wild Wind

Jib Kidder is the performing moniker of musician and artist Sean Schuster-Craig. Born in Lousiville, raised in Georgia, educated in Michigan and bouncing between California and New York ever since, he has spent the last decade exploring a variety of approaches to psychedelic collage. In his audio recordings, songs, videos, sculptures, digital paintings, chalk murals & written work he has attempted to harness the humor and ambiguous poignancy specific to the experience of dreaming.

Collage

The first art I ever made was collage. I traced raccoons as a Catholic toddler in Jewish daycare. Later, In High School, I skipped class to make collages on the library photocopier. Collage shares much with dreams. I was always better at the sideways thinking of humor, of dreams, than with rational logic.

Guitar

I started to play guitar after my friends and I were the first kids in our St. Louis elementary school barred from performing in the yearly talent show on account of our not taking ourselves serious enough. We were determined to blow everyone away the next year and began to study our instruments. When I was 13 I moved to Georgia and acquired a new guitar teacher, Jimmy. We had a lot in common and came to think of each other as relatives, as cousins. We both played drums to the music constantly playing in our heads by gnashing our teeth. Jimmy thought I had some genius for the guitar and ran out of things to teach me in about 6 months. At that point he suggested I study Classical and play with his band. So that year I began to play bars in Atlanta and learned a lot from older players.

Around then a dose of Mexican speed landed Jimmy in a psychiatric hospital. From there, he phoned my father, expecting understanding, perhaps because my parents are also musicians (my mother, an opera singer and my father, an organist/pianist/musicologist). Instead, I wasn’t allowed to see him anymore. Jimmy recovered soon after and increasingly pursued a sort of spiritual recovery. He quit teaching guitar – I took over his students. I never told my students how old I was – by then 15. Later, when I could drive, I joined Jimmy’s band again. The other players in the band (home recording savant Ben Lawless and documentary filmmaker Matt Miller) turned me on to a lot of music with more nuance than what I had been listening to prior. They opened my ears to international folk/pop, underground thug rap and country/western records. Matt had been filming Ya Heard Me?, his documentary on New Orleans Bounce music, and he was bringing incredible records back to Atlanta from NOLA. Meanwhile, Lawless and I were stealing answering machine tapes from thrift stores and grafting them on 4-tracks.

One day Jimmy asked me and Lawless what our birthdays were. This had something to do with an oracle he was using in the hippie commune he lived in where I took acid sometimes and once saw an Emu fuck a Llama or probably vice versa. The next time I saw Jimmy his eyes were black and he was rocking back and forth, parked in his van in front of my house. He moved into my Atlanta apartment for 3 weeks, doing little but staring at the wall. He never told me what happened. I was too young and stupid to be of help. My other friends got addicted to meth, which at the time was hitting Georgia like a plague. Tweekers were stealing my music gear. One friend of ours went home after a meth binge and accidentally smothered her infant while sleeping. So I moved away. I gave up the guitar for years. I’m still not as good at playing as I was as a teenager. I have never made complete peace with the instrument.

Computers

Acquiring my own computer accelerated my progress in writing and recording. I was already obsessed with the 4-track, but the computer opened countless doors. I liked to work alone. I liked to work all the time. And with the internet I could teach myself. I was always irritated with cops, with doctors, with bosses. In many ways I was born an autodidact.

Sampling

My first computer music was just general MIDI programming and recorded toy keyboards. It seems a weirdly constrained palette to me now, but it worked for a time. It offered a further level of zoom. You could determine the big picture and watch the details emerge instead of determining the details and watching the big picture emerge. Around 2005 or so I finally figured out how to easily sample existing recordings. I was entranced. Dreams sample the stuff of life to form chimeras. Now I could construct dream chimeras from the stuff of my life of listening. I was always against money, against gear, against bullshit. I had absorbed some zen philosophy from Jimmy (who had given me a copy of the Tao Te Ching and introduced me to sitting meditation) and punk philosophy from the first creative low fidelity recordings I encountered like Sebadoh III, Beck’s One Foot in the Grave, Sonic Youth’s Bad Moon Rising and Daniel Johnston’s Hi How Are You?. Later, when I was discovering sampling, I was listening almost exclusively to underground Southern rap and conceptual or improvised music. So I went to work combining these things and spent years making my first proper release All on Yall. I was using a shitty Windows PC clone I’d had since Y2K.

Radio

After leaving Atlanta, I studied American Culture at the University of Michigan, though I didn’t do anything in college but hang out at the radio station, WCBN. I would listen to records there, endlessly. I would take entire alphabetical sections of the music library into the listening room and demo them all. I actually lived in the radio storage room for a while. I would use radio supplies to make CD-R releases in editions of two, gutting unusable promos for their jewel cases, selling them to the record store to buy a pack of cigarettes. At the time, Julia, Laurel Halo, and benoît pioulard were all active at the station. Our close mutual friend Jeffrey began recording his own music around that time too. He had a deep interest in animals and would at times rehabilitate injured ones in his home. He made gentle music that seemed to explore a kind of animal consciousness. Julia has said it was Jeffrey and I who had turned her on to home recording, initially.

Dark Years

I had spent years studying music and obsessively making my own recordings but no one knew me and I was moving around with my girlfriend to various expensive cities for her work as a scientist. I took on low-paying jobs to try to support myself. I laundered bloody surgical towels and the pissed-in bedsheets of children from group homes, delivered lunches on bicycle to movie studios, worked in an assembly line which produced patient food trays in an industrial hospital kitchen. My drinking, which had been bad enough, worsened. My stomach was bad, had been bad for years. It was hard to leave my house because I could become sick unpredictably. I got a repetitive strain injury from my industrial hospital job resulting in a later abandoned workers’ comp case as cruel as it was hopeless.

An Epiphany

Around then some professional dancers discovered “Windowdipper” and the track ended up on the Fox competitive reality show So You Think You Can Dance. I got a little chunk of money for the first time for doing something I loved instead of crumbs for doing something I loathed, and I had to quit my job anyways to preserve my hands. It occurred to me that my music had the potential to get inside other people. People unlike me. To get inside their bodies even. I moved to LA. I had no day job anymore, I could read and work on music as much as I liked. It was amazing. I got deeper into making videos and paper collage. I learned how to cultivate a free feeling. The Asthmatic Kitty label reached out and generously delivered their entire catalog to me for free sampling. I got into singing again. Singing was about being less withdrawn and also about engaging the brain’s word parts. I began to perform vocally and immediately there was interest in the audience that had been absent prior. I had grown a deeper interest in older country music, like Webb Pierce and Conway Twitty, through working on my collage record Steal Guitars. Before then I hadn’t been listening to any vocal music and so I never wrote vocal music.

A Resolution

I ran out of cash though and I needed to see a doctor. I didn’t have insurance. I was having other people fake illness to obtain prescription meds, even though it resulted in the wrong dose. I moved to Oakland to reunite with my girlfriend. I got a call center job for the insurance. I quit drinking, quit cigarettes, signed up for a 420 Evaluation. I ate dispensary edibles on my lunch break and via telephone headset helped the elderly regain access to their online accounts. My best friend called me from prison one day and turned me onto Gertrude Stein’s Making of Americans. It was the most musical thing I had encountered in written language and it opened my mind to how you could use language as notes, as paint, how you could use repetition to weave simple parts into a greater complexity. I started writing the songs that would be Teaspoon.

Dreams

The last time I spoke with Jimmy on the phone, he told me dreams were my entry point to the world of spirits. I have always been fascinated with their realm. As a child, 8 or 9 years old, I dreamt of two lucky number sequences: 72543 and 54723. I developed a circular arithmetic explanation for them which I believed explained their energy, revealed their power. I started to use my lucky numbers to wish for things. That a girl would fall in love with me (usually did work) or some likely crisis would be averted (almost never worked). I would cross my middle fingers over my pointer fingers, fold them into a fist, state my wish and my numbers 5 times, once for each human finger. Those lucky numbers appear in much of my work, either visible in the artwork or concealed in the music’s form, to imbue it with charm.

I started to write down my dreams when I was 14, and started to lucid dream when I was 18. I would stick on a nicotine patch, set five alarm clocks and go to sleep at 8 pm. It was around then I was starting to make my first small edition CD-Rs and had a dream where I could see clearly on the cover of a jewel case above a painting of an amputee with open wounds, the words “jib kidder”. This is where the band name comes from, which I consider neither a first and surname nor meaningful words of another kind. This is also how I have come upon my aesthetic ideals. I prefer art to assume the form of dreams. To be poetry, indecipherable poetry, made out of the stuff of your waking experience. Dreams have their own rules, and I use these as rules of form. Every person in a dream is many people. Every word is many words. The flow of action seems at odds with the flow of time. Things fold into each other. There are no resolutions – dreams are ongoing. Their logic is lateral, never critical and their focus is sexual and anxious.